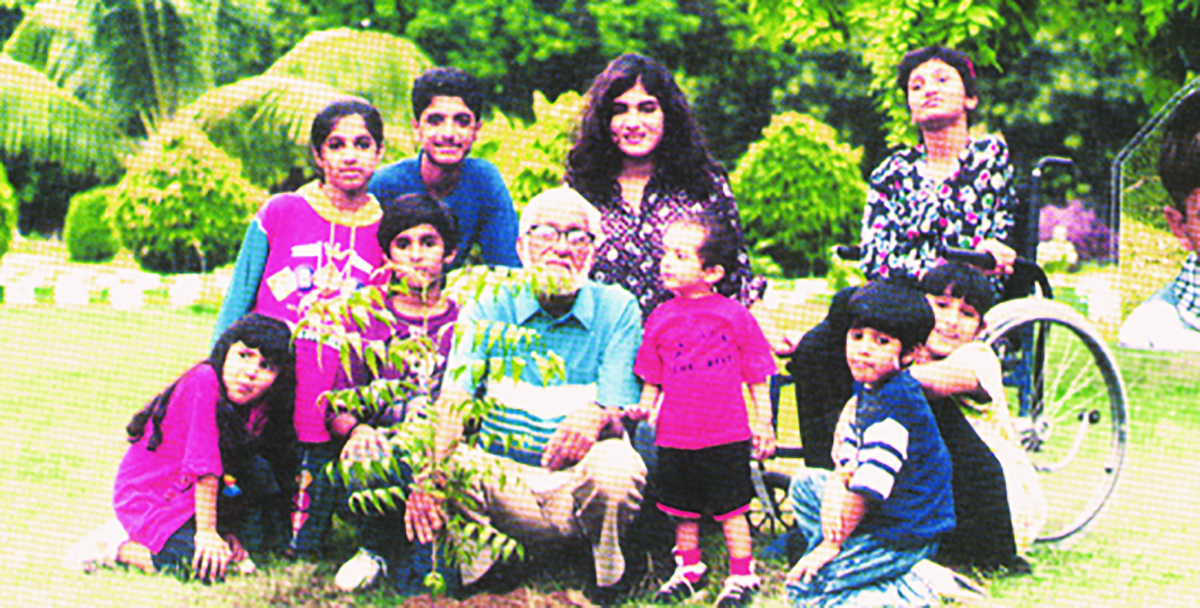

Mr. A. K. Khan was an eminent horticulturist of Pakistan, known as "Baba e Baghbani Pakistan". His forefathers migrated from Afghanistan and settled in Amer near Jaipur where he was born in 1919. He graduated in Horticulture from Allahabad University in 1944. After graduation his first appointment was in Kabul, Afghanistan, later he worked in Agriculture Department Delhi. He opted for Pakistan well before partition in early 1947 where he served in various capacities including Pak PWD, Government of Pakistan and retired as Director, Parks and Recreation from Karachi Metropolitan Corporation. He was elected Member International Committee for Horticulture Nomenclature in 1952 at the 13th International Horticultural Congress and in 1984 he was elected Member, Landscape Institute, UK. His passion for horticulture induced him to establish the Horticultural Society of Pakistan in 1948. He received the President's Award for Pride of Performance in 1990 in the field of Science and Sitara e Imtiaz 2010. He is pioneer in Horticulture in Pakistan designed hundreds of mega projects, trained educated ladies, gents and malies. He has six books to his credit.

He passed away at the age of 96, on 6th September 2015.

"He was a tall upright tree. Many saplings grew into big and strong trees under A.K. Khan’s guidance"

Mehtab Akbar Rashdi

Tribute paid to late horticulturist A.K. Khan

The seasoned horticulturist passed away at his home on Sept 7.

Flashback: An evergreen shade

KHAN SAHIB

The twinkle in his eyes

By Durdana Soomro

I first met Khan Sahib in January 2000. I had just returned back from the UK and was laying out my garden and, with the enthusiasm of the newly returned, wanted to find out about organic pest control. Someone suggested I go and see Khan Sahib as he was the authority on horticulture. So off I went to his office, which at that time was behind the National Bank of Pakistan in Clifton. I found myself in front of a grave and intimidating white-bearded gentleman. I asked him about organic pest control and, like a doctor, he immediately wrote out a prescription involving neem, tobacco, naz boo and marigold leaves. Then I told him about the ants infesting my garden and he suggested pouring boiling water into the holes. But I was reluctant to try that especially where the ant heaps were too close to plants. Very timidly I asked if there was nothing else I could do?

He looked thoughtful. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘you could always get an anteater. But they are such ugly creatures.’

I was a bit taken aback – until I saw the twinkle in his eye! That was when I realized that unlike many of the intellectuals and experts one sees today Khan Sahib was cut from a different cloth. Behind his serious façade was a dry, very English sense of humour.

I immediately joined the HSP and got to know him more closely in the years to come. Always fastidious about his appearance he favoured western clothes and whenever he came to HSP meetings was invariably dressed in a crisply ironed shirt and trousers, or a suit and tie. In his erect bearing and aquiline features was the shadow of his Afghan ancestors. They had been brought as prisoners of war from Kabul by Raja Man Singh and settled on the outskirts of Amer (Amber), once the capital of Jaipur State. One or the other of his forefathers had worked on the important gardens of Rajasthan, including the Ram Bagh palace gardens and the gardens and fort of Amer. For Khan Sahib to go into horticulture was inevitable. He practiced it for over seven decades, founded horticultural societies, taught thousands about gardening, wrote several books, including the iconic The Gardener. But he did it all for passion; money never meant much to him. His aims, as he revealed to me when I interviewed him for an article (Books & Authors, Dawn, July 8, 2007), were much loftier. His principle was that no matter what you do, you shouldn’t be content unless you became the best. ‘Be a cobbler, be a dhobi, but you should be the last word. Your aim should be to acquire knowledge in the subject. People should come to you.’

At the tribute paid to him recently someone mentioned that everyone who was close to Khan Sahib felt that he or she was special in his eyes. I too felt that he had a soft spot for me, just as I had for him. Khan Sahib was a rare individual: despite the high esteem in which he was held, he was a humble and soft-spoken man. He was also a workaholic. The work ethic was inculcated in Khan Sahib from a very young age. As a young man he had studied in the Allahabad Agricultural Institute. This institute was set up by American Presbyterian missionaries to provide agricultural training to Indians. In his autobiography he describes the practical work the boys had to do. Each one was allotted a pair of oxen and a plot of land measuring 200x200 feet which they had to cultivate. One day, noticing that his crops were not flourishing, his professor W.B. Hayes offered to send him extra manure. The following week when Hayes saw him working on the plot he asked why he hadn’t applied the manure. Khan explained that he hadn’t received it yet. Hayes pointed to the manure lying in in a heap across the street. Khan was surprised. ‘Do you want me to bring the manure from there?’ he asked.

‘No, my son,’ the professor replied gently and walked away. A few minutes later Khan saw the old man bringing the manure himself in a basket. He rushed over in great shame and apologized profusely to which Hayes responded: ‘You have only been here for a year. In four years you will value the dignity of labour.’

It was a lesson that he never forgot. He came to his office at the Garden Centre and continued to attend meetings and preside over his beloved flower shows until he died. The title of his autobiography Rau Mein Hai Rakhshe Umar proved to be very apt. It’s from a verse by Ghalib:

Rau mein hai rakhshe umar kahan dekhiye thamay

Na hath bag par hai na pa hai rikab main

The steed of life runs on. None knows where it will stay its course

The reins have fallen from our hands, the stirrups from our feet

–Translation by Ralph Russell

The steed stopped but Khan Sahib remained in the saddle till the very end.